License to Own: The Illusion of Digital Property

The Cambridge Dictionary defines “ownership” as

the state of fact of owning something.

“Owning”, by that same logic, is defined as

belonging to or done by a particular person or thing.

Ownership is the cornerstone of all the world’s capitalist societies. This is most palpable in the United States, where people almost equate purchasing power with personal worth, and fiercely, oftentimes violently, protect their right to ownership and property as an inviolable, unassailable right.

Last time a group of people in America wanted to maintain ownership over something they believed (incorrectly) was their right to have, the Civil War happened.

This concept, however, has slowly been eroded through the years.

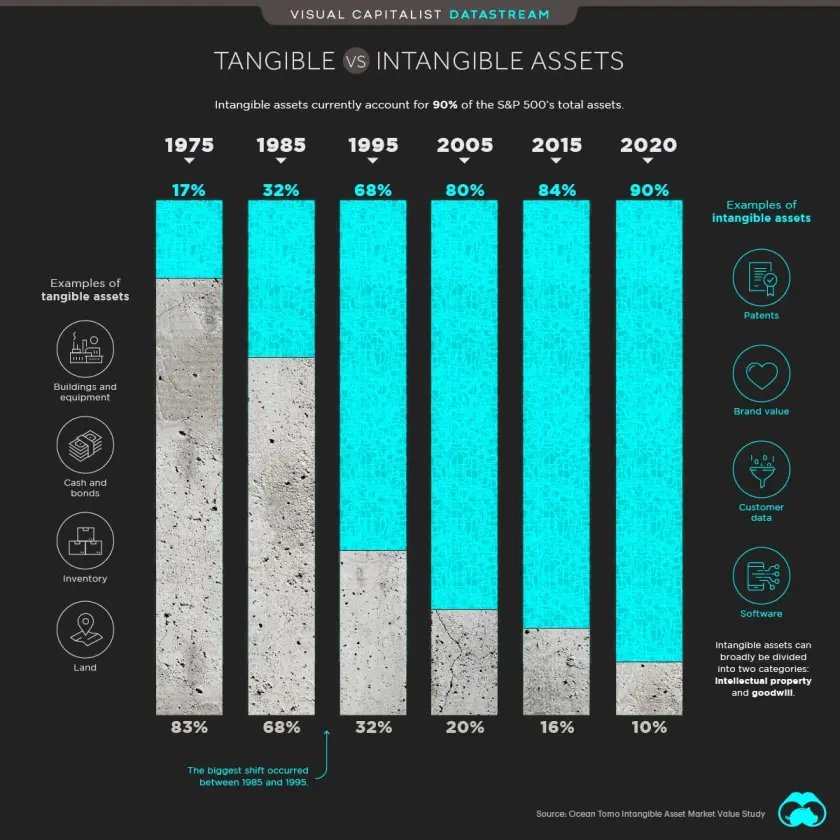

What it means to actually “own” something has become an ever-increasing grey area, especially when you consider some of the biggest markets in the world right now don’t have anything to do with the physical world. As of 2020, intangible assets accounted for 90% of the S&P 500’s total assets.

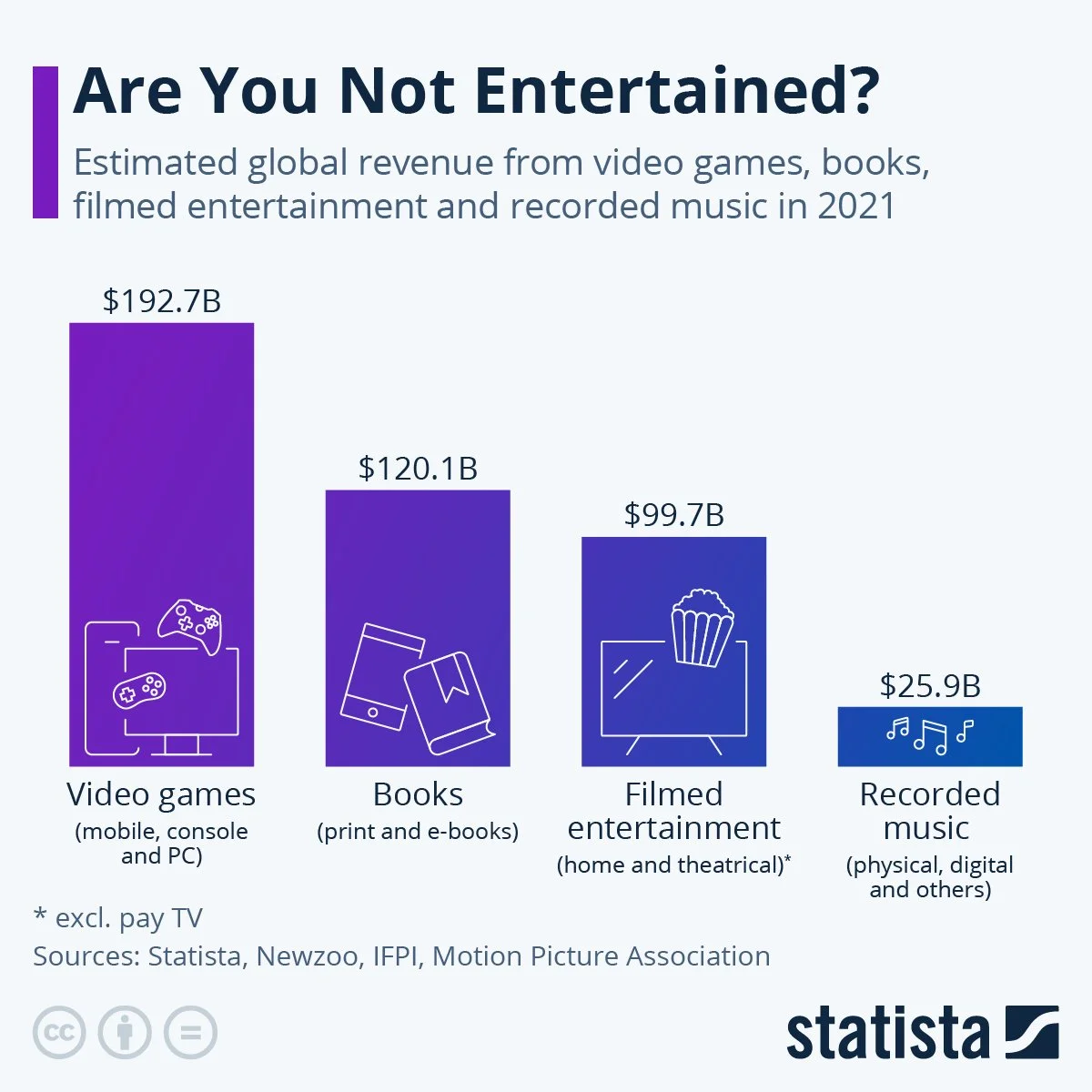

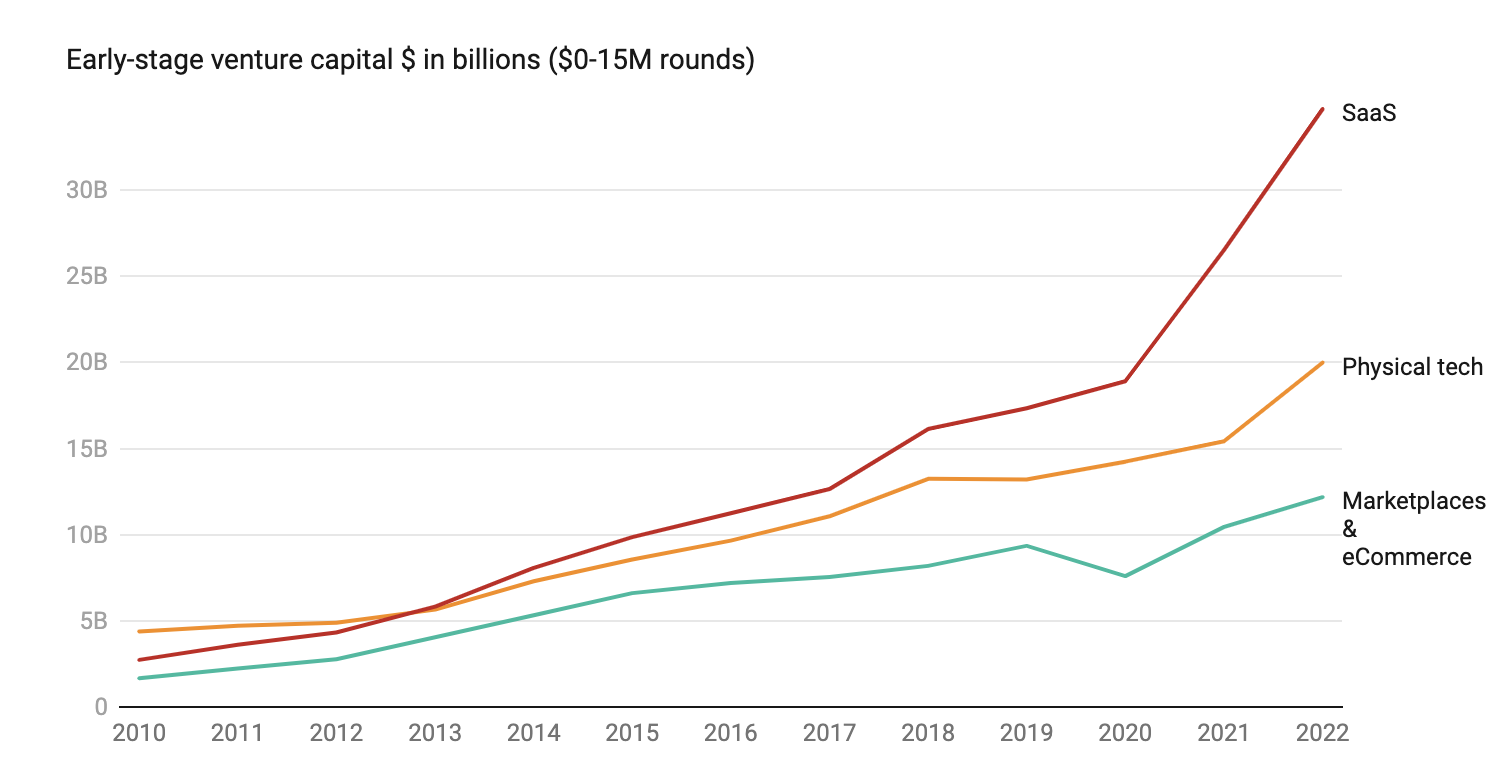

Most of these companies don’t produce any tangible “products”, but instead deal with “digital media”, which covers everything from music, film/TV, software, books, video games, and more. These industries, especially in the entertainment sphere, have grown exponentially in the last 10 years, cornering large swaths of the market, measurable in the realm of billions of dollars.

So when did this shift start?

You could argue it’s been ongoing since the dawn of the first personal computer, the Konbak-1, in the early 1970s.

After all, any computer needs software to run on it, and with the advent of software, something inherently intangible, the natural progression of things was that companies cere created who specialized in it.

However, none of this rapid advancement in the digital space could have been possible without the power of the internet. Specifically, broadband. The early internet in its nascent stage–the era of that unforgettable piercingly chirpy dial-up noise—was slow and incredibly inefficient. Not even on its best day could it have sustained the level of information that is traveling around the globe nowadays. Available speeds were glacial and the options for data storage came in orders of magnitude the size of entire rooms instead of the ultra-slim hard drives and solid-state drives we use today.

Only after the development of DSL and cable broadband in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and after data storage methods became more cost- and space-efficient, did the world really begin to understand, and actively make use of the scope, and power, of instantly available information and content. We had the privilege of inviting the world inside our homes one data packet at a time, and companies with their monetary goals joined in.

Once the versatility of the digital space really started to become understood, especially when the revelation that reams and reams of paper data could be converted and stored digitally using a fraction of their physical space and “beamed” all over the world, easing or even outright erasing communication hurdles, there came another revolution.

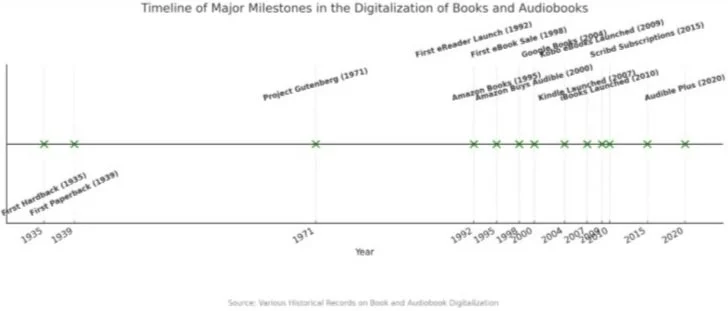

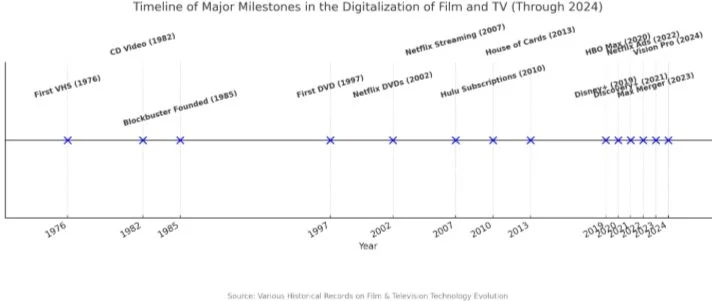

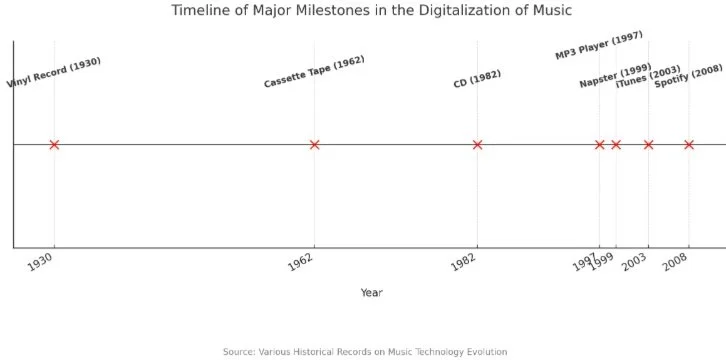

Things that were squarely only within the “physical realm” suddenly started to become digitized and miniaturized with ever-increasing velocity. The rapidity of this evolution can be clearly seen by the absurdly shortened development time between different mediums in comparison to the large swathes of time between every development that came before. The industries most famously impacted by this were music, film/TV, and books.

In the beginning, the digitalization of all of these products was massively convenient to the consumer and so, understandably, they saw a massive boom of popularity. You could now carry the entirety of your entertainment library with you wherever you went.

Content from around the world was available at your neighborhood video or music store from one day to the next, and, eventually, just a simple click away on your favorite streaming site.

Not too long before this, you would’ve had to go out and buy an entire set of 13 floppy disks just to install Windows 3.1.

These new tools and methods of communication fostered an unprecedented cultural revolution.

These years of massive global interconnectedness within our media and pop culture brought on phenomenons like The British Invasion in the 1960s, The Korean Wave (Hallyu) which started in the 1990s and is still at a fever-pitch today, The Japanese Wave that is currently in a phase of growth, and the most recent emerging cultural wave, Afro beat and Afro futurism, among others.

In many ways, the globalization of culture via the internet had a positive impact on society as a whole. Several studies suggest that exposure to diverse and international content—whether through books, movies, music, or social interactions—can increase open-mindedness, empathy, and acceptance of different cultures.

A study published in BMC Medical Education found that individuals with higher levels of open-mindedness are more likely to engage in cultural immersion, thereby enhancing their intercultural communication skills.

Research involving 856 Chinese TV series viewers revealed that consuming cross-cultural media products strengthens bilateral relations and fosters favorable attitudes toward the target culture.

A study on YouTube consumption patterns found that cultural values significantly influence a country’s openness to diverse content, suggesting that exposure to international media can enhance cultural openness.

Research published in the Journal of Judgment and Decision Making demonstrated that individuals with actively open-minded thinking are better at interpreting and reasoning about social media content, indicating that open-mindedness enhances engagement with diverse perspectives online.

All of these are excellent things.

However, if the digitalization of media has all of these positives going for it, then why did we begin this analysis outlining the definition of ownership?

That’s because, as greater and greater slices of the world’s market economy are being taken over by this global interconnected web of media that only exists in this intangible place that is the internet, companies have inevitably begun to worm their way into making more and more money by controlling and manipulating the access consumers have to this material.

The harsh reality is that the internet is not a public good.

To gain access to it, you need to pay for someone. To explore it, you use the service of a company whose goal is to earn money from your experiences even if at face value the service they offer is “free”. Most importantly, all the entertainment you consume needs to be created, stored, and streamed by someone, oftentimes multiple parties, all who own slices of that content.

Every single one of these entities seeks to recoup their expenses from you, the consumer.

There used to be a day when you could buy a movie, CD, cassette tape, book, etc., and then you owned it. You had a physical representation of that content and you could do what you wanted with that object. You could play the CD in your car, in your Walkman, in a boombox in the park, and all of these mediums (the CD, the car, the Walkman, the boombox) where things that you “owned” and that you could then use, loan, or even resell in perpetuity until they either failed or broke.

The creator of that piece of entertainment, let’s say the musician to stay with the example of the CD, would get paid a portion of that one CD sale when you first bought it from the store, and the rest of their income would come from how many radio plays the song got, or any concert tickets or merch that they sold during their release tour. It was a straightforward process that consisted of a more or less direct sale from producer to consumer (in this case, the artist, via their music publisher, to you, the listener with the store as a middle man.)

With the advent of digitalization, entire “middle man” companies rose up to become the premiere, sometimes even in the only way, a consumer would be able to access and experience their content. No industry was more greatly affected by this than film and TV with the rise of streamers and every business model that shaped their business model after them.

Sure, even back in the day, you knew that whatever piece of entertainment you brought home with you might not physically last forever when you purchased it. Plastic / metal / silicone / magnetic film, etc., all have a very real shelf life. But the assumption was that the medium itself is what would decay, rendering the content “non-consumable”. What wasn’t called into question was your ongoing ownership of that copy of the material, no matter its state. There was no real doubt that even if you owned an unwatchable copy of a VHS tape of a certain film, you still OWNED a copy of that film.

In these last few years, unfortunately, owning anything in the digital space is uncertain at best, and impossible at worst. This goes far beyond just movies and TV shows, though. Software companies, too, have rapidly moved away from the standard purchasing business model. Nowadays, there is rarely a way to buy software outright. More than 90% of all creative software and 85% of all enterprise software are now only sold on a subscription model.

Rarely, you’re able to find services that offer “Lifetime Licenses” at a much higher price, which they say guarantees you access to each new version of the software in perpetuity. Even then, though, the small print might mean that the rules could change any moment it suits that company. If so, that might be the point you realize their concept of a lifetime is much shorter than you expected.

I’ve experienced this myself. One day, a perfectly functioning software I had bought once and then re-downloaded / reinstalled in many subsequent machines after they died stopped being available. I was outright prevented from downloading the product I had specifically purchased. The only possibility they offered was the “new and improved” version that, of course, was only sold via a much more expensive subscription model. When I reached out to the company pointedly inquiring why an item that I had legitimately purchased was suddenly not accessible to me anymore, I was informed that they would send me a single download link to the disc-image file of the “legacy” software I’d been using but that after that it would be up to me to maintain the file’s integrity because they were no longer going to provide it to anybody after a certain date. Mind you, this software was still compatible with current operating systems and functioned perfectly. Just like that, something that I had owned for years was taken away without my consent or knowledge. To use that piece of software again with a different computer, I would need to spend more money on the latest version via yet another subscription, or find a safe way to store the software in the cloud myself.

The most insidious thing out of this shifting philosophy of digital content means something that you thought you had spent your hard-earned money to own, whether that be a piece of software, a movie, a season of a TV show, or a music album, could disappear without a trace, and there would be nothing you could do about it.

While of course this directly impacts consumers in a big, obvious way, the effects and damage it’s wreaking on the creators of the content themselves is also definitely worth talking about.

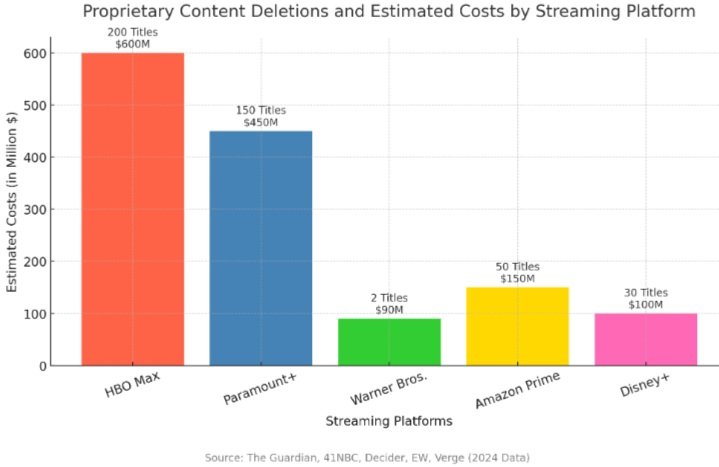

n 2024, HBO’s streaming entity, Max (once HBO Max / HBO Go) deleted 200 titles of their content from their platform. This wasn’t a case of distribution licenses running out or contracts expiring en masse. These 200 titles were owned, produced, and distributed by HBO (which is a subsidiary of Warner Bros.). The worst hit was their animation slate. Old classics and new amazing projects alike, gone without a trace. Of course, since most of this material was made for streaming, no hard copies had ever been made, nor had there been any plans to make any.

After all, if it’s on the internet it’s forever, right?

No matter how true that might be for embarrassing viral moments or memes, the reality for creative content is vastly different.

Within the span of six months, the whole crew behind the TV show Willow, a 2022/2023 sequel to the 1988 classic starring Warwick Davis, saw what was likely months, if not years, of their work disappear overnight when Disney+, who owned and had produced / green-lit the show, decided to completely pull the first (and only) season off their platform for “cost-cutting measures”.

Since it’s a Disney+ property, and no outside party distribution licenses have been issued thus far, there is literally no legal way to watch the show anymore. It’s just gone. Anyone who worked on it, maybe for their hard-fought first-ever job in the industry, and had hoped to use the project as a calling card for finally launching their career, now had nothing in hand. Aside from the pure unfairness of it all, this is also a terrible precedent for the concepts of freedom of speech / expression, a person’s right to access information, and the ability to take part in open dialogue and critical thinking.

Sadly, it gets worse.

It’s in frustrating moments like these when it becomes ever so clear that even though you’re a paying customer, it’s absolutely up to these companies how and in what manner they give you, or don’t give you, access to their content. It doesn’t take long for serious worries about censorship to take hold.

Amazon, the company the world loves to hate (rightfully so), announced last month that by February 26th, 2025, it would discontinue the Kindle feature on their website where you could download any ebooks you bought and transfer them to a device via USB cable. The important thing to note here is that while of course this feature was intended for, and most frequently used by, Amazon Kindle users, this action, at the time, was not limited to Amazon products. Many readers around the world would buy ebooks on Amazon (which would oftentimes be the only retailer with the content available), then use this feature to read them on their own preferred non-Amazon e-reader. This latest crackdown on multi-device compatibility, thinly veiled as an excuse to fight piracy, is Amazon’s latest attempt to keep you permanently locked into their systems.

If you can buy only from them (Amazon the most powerful e-commerce company in the world), and access their content only from them (they also own Audible, the only real competitive audiobook producer and retailer), then you are subject to their will regarding all of their content.

Instances of unchecked censorship by Amazon have already happened.

In 2023, children’s author Roald Dahl’s publisher, Puffin Books (the children’s imprint of Penguin Books), decided to expurgate various of his works. No matter how you may personally feel about Dahl, his views, his books, or their content, not only was this against the express wishes of the late author, but this was also done without the consent or knowledge of his estate. The same was subsequently done for the works of Enid Blyton (author of The Famous Five) and Ian Fleming (of James Bond fame). Worst of all, this also took place with R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps’ series. This time around, the author was (and is) still alive and well. His work was still1 expurgated without knowledge or consent.

Amazon's Kindle currently dominates the e-reader market, holding a substantial 72% share. Additionally, Amazon leads the eBook market with 79% of all purchases in the US, followed by Barnes & Noble at 29% and eBooks.com at 28%. While physical books are still the preference for now, e-reader users are expected to reach 1.2 billion by 2027.

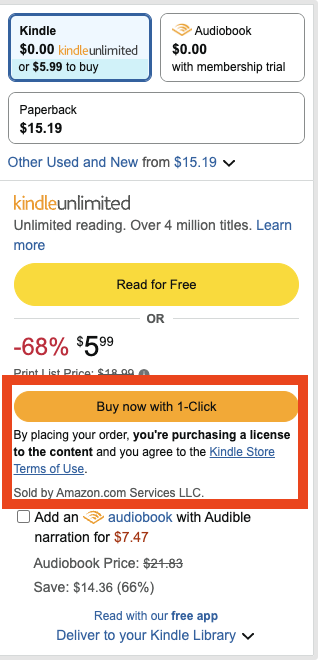

That’s 1.2 billion people that might have their books modified, or even completely purged with little to no warning and definitely no consent. This is ever more clear by the new language Amazon Kindle has added as of December 2024 to every book’s storefront page,.

“By placing your order, you're purchasing a license to the content and you agree to the Kindle Store Terms of Use.”

One section of this very long contract is most illuminating about what freedoms Amazon feels they have with the content you “buy” from them:

“Changes to Service; Amendments. We may change, suspend, or discontinue the Service, in whole or in part, including adding or removing Subscription Content from a Service, at any time without notice. We may amend any of this Agreement's terms at our sole discretion by posting the revised terms on the Amazon.com website. Your continued use of any Kindle Software or any aspect of the Service after the effective date of the revised Agreement terms constitutes your acceptance of the terms.”

Once again, this is stark proof that if you buy an ebook (or any digital media) from Amazon, you’re not actually owning, or buying, anything at all.

If something you "own" can be taken away at any moment without your consent or awareness, then that ownership is a lie you tell yourself perpetrated by a company for whom it is convenient that you keep thinking that way.

So two questions remain: Why? And how is this even allowed?

Unsurprisingly, all of this is largely driven by financial incentives—subscriptions provide a steady, predictable revenue stream, while licenses allow companies to maintain control over their intellectual property and limit unauthorized distribution or resale, usually by way of DRM (Digital Rights Management). Digital distribution makes it easier to enforce these models, as physical ownership is being gradually replaced by access rights controlled by the provider.

However, no matter how many companies like Amazon push it onto their products, there is ample evidence that DRM is a failing idea. It often punishes legitimate consumers more than it deters piracy. Digital pirates inevitably find ways to bypass DRM protections, while paying customers are left dealing with restrictive limitations, such as the inability to access content offline, compatibility issues across devices, recurring performance issues due to memory-heavy or buggy DRM systems working in the background (especially in video games), and the risk of losing access if a service shuts down.

DRM also creates unnecessary dependencies on online verification servers, meaning that even legally purchased content can become inaccessible if whatever third-party company had been contracted to provide that server decides to revoke access or discontinue support. Furthermore, history has shown that heavily DRM-protected content still gets pirated, often leading to a situation where the pirated versions are more convenient and user-friendly than the legitimate ones. This not only frustrates paying customers, but also heavily undermines trust in digital purchases, pushing users toward alternatives that don’t impose such restrictions. In the long run, DRM does little to stop piracy while creating friction for honest consumers, making it an increasingly ineffective and unpopular approach.

Legally, this library-style “long-term rental disguised as ownership” strategy companies are taking is upheld by terms of service agreements which users must accept before gaining access to content or software—those extremely long documents nobody really reads that pop up every time you start using a new service.

These agreements typically clarify that consumers are purchasing a license to use the product, rather than outright ownership, and that the provider retains the authority to modify or terminate access under specified conditions, which can be as vague and undefined as the provider wishes them to be. Users agree to these terms when they subscribe or make a purchase, effectively entering into a contract, sometimes unknowingly, that prioritizes the company’s control over the product over their own right of ownership.

Not only does this system make sense for companies from an economic perspective, since it makes them a lot of money on a more consistent basis, it’s also completely legal. We, as consumers, are the ones that give them permission to carry on in this manner every time we accept any terms of service agreement and all of its caveats.

Source: Spendesk

This pronounced shift over the concept of ownership fundamentally changes the relationship between buyers and sellers, replacing the traditional idea of property—where purchasing an item grants full control and indefinite use—with a model where access can be revoked, altered, or restricted at any time. As digital media, software, and even hardware become more reliant on online verification and licensing agreements, consumers face increased uncertainty about the longevity of their purchases.

Additionally, it creates an environment where people are perpetually tied to subscriptions and ongoing fees rather than making one-time purchases. In the long run, this could easily lead to a future where we, as a collective, have lost our personal autonomy over digital possessions, forcing us as consumers to continually pay for access to things we once would been able to own outright.

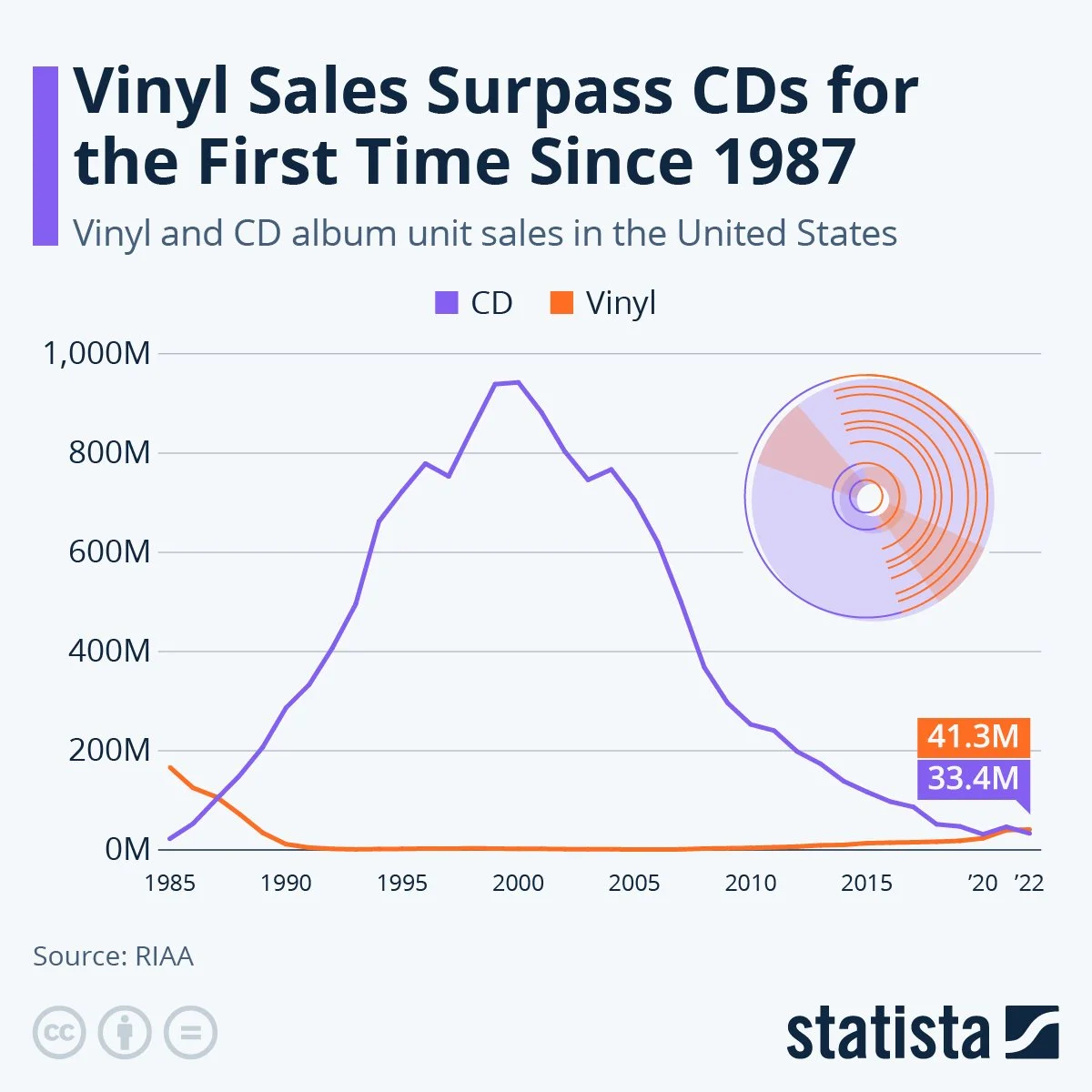

One silver lining at the end of the tunnel is that as digital ownership becomes increasingly conditional and uncertain, there’s been a resurgence in the appeal, some might even say even the cultural necessity, of physical media.

Many consumers are turning back to physical formats like DVDs, Blu-rays, vinyl records, and print books because they offer true ownership like the kind they, or their older relatives, remember.

This shift is driven not only by nostalgia but also by a growing awareness of the impermanence of digital libraries—especially as companies have begun removing purchased content from platforms or forcing consumers into subscription-based models.

Physical media also continues to often provide superior quality, such as lossless audio or uncompressed video, further enhancing its value. As a result, maybe a bit ironically, the rapid trend push from companies to direct us all towards an ownerless future has led many to seek out tangible, collectible, alternatives that grant them true permanence. While the convenience of digital media is undeniable, the reassurance of holding a physical copy in your hands—one that can’t be erased by a corporation’s whim—is proving to be an increasingly valuable commodity.

So, where does that leave us?

Well, in a world where the very concept of ownership is being leased back to us one subscription at a time, perhaps it’s time to embrace the modern pirate’s mantra: If you love something, set it free—preferably in a format that doesn’t require a server to acknowledge your existence.

Otherwise, you might wake up one day to find that your favorite movie, TV show, book, or software has vanished into the digital ether, taking your hard-earned dollars with it.